← Back to Research

January 29, 2026

Loss of First Principles Science with Agentic AI

Written By

Abhinav Sinha

Topic

Agentic AI

Category

Research

Read Time

10 min

There is an innate human desire for immediate causality. Software engineering is built on that feeling: write a test, find the bug, fix it, watch it pass. There's a satisfaction in that loop, the kind that comes from pushing a lever and watching gears turn.

In the stochastic world of AI agents, that loop stops working the way it used to. A passing test might quietly fail the next morning. The instinct to fix and move on still feels right, but it starts to mislead you. What feels like forward motion is often just lateral movement.

"The fastest way to improve a system you don't understand is to measure it carefully. The most common way is to change something and see what happens."

This "change things and see what happens" mindset rarely survives in frontier research, but a strange collision is happening right now between research and industry. Usually research runs years ahead, with practical adoption trailing behind, but with agentic AI, enterprises saw the value immediately. At NeurIPS (the leading CS conference) this year, most projects were testing the boundaries of LLMs and agentic systems, which is exactly what enterprise teams are racing to ship. The pressure compresses from both ends: researchers shorten timelines to chase benchmarks, engineers find themselves doing state-of-the-art research without the time or training for it.

Somewhere in this race, the first-principles rigor that produced modern models got left behind. What follows are the failure modes I've seen emerge from this gap, and some thoughts on how to close it.

As an aside: if you're interested in the basics of building an agent, I recommend Mastra's books. If you're already past that stage and want to set up the first step of the scientific process, Anthropic's piece on building golden datasets and evaluations is a solid reference.

Principle 1: Hidden Overfitting

The basics of model training are a good example of first-principles thinking in action. When a neural network misclassifies a black dog as a cat, you can't open it up and fix the weights. You need to make an educated hypothesis. Maybe the dataset needs more examples of black dogs? Maybe the class distribution is imbalanced? Whatever you try, you test it against data the model hasn't seen before, because there's no other way to make sure your fix actually worked.

During agent testing, it feels different. You can open the trace and see exactly where things went wrong, and when you make a change, the change itself is visible. This sense of control makes building a held-out set feel like a waste of time.

Current State of Golden Datasets

The agent improvement pipeline has recently become quite standardized as teams concluded they need a "golden dataset" (defined by Arize), which is a dataset with trusted inputs and ideal outputs, typically hand-labeled by humans, that serves as a benchmark for model output quality.

The purpose of this dataset varies from team to team, but some of the common ones we've seen are: (1) CI/CD integrations to ensure agents don't regress, and (2) benchmarking suites. Overall, it's pretty analogous to unit tests, but so is the assumption underneath: improving on these cases means the agent is getting better.

Sierra's τ-bench suggests it might not be that simple.

Test Cases as Distributions

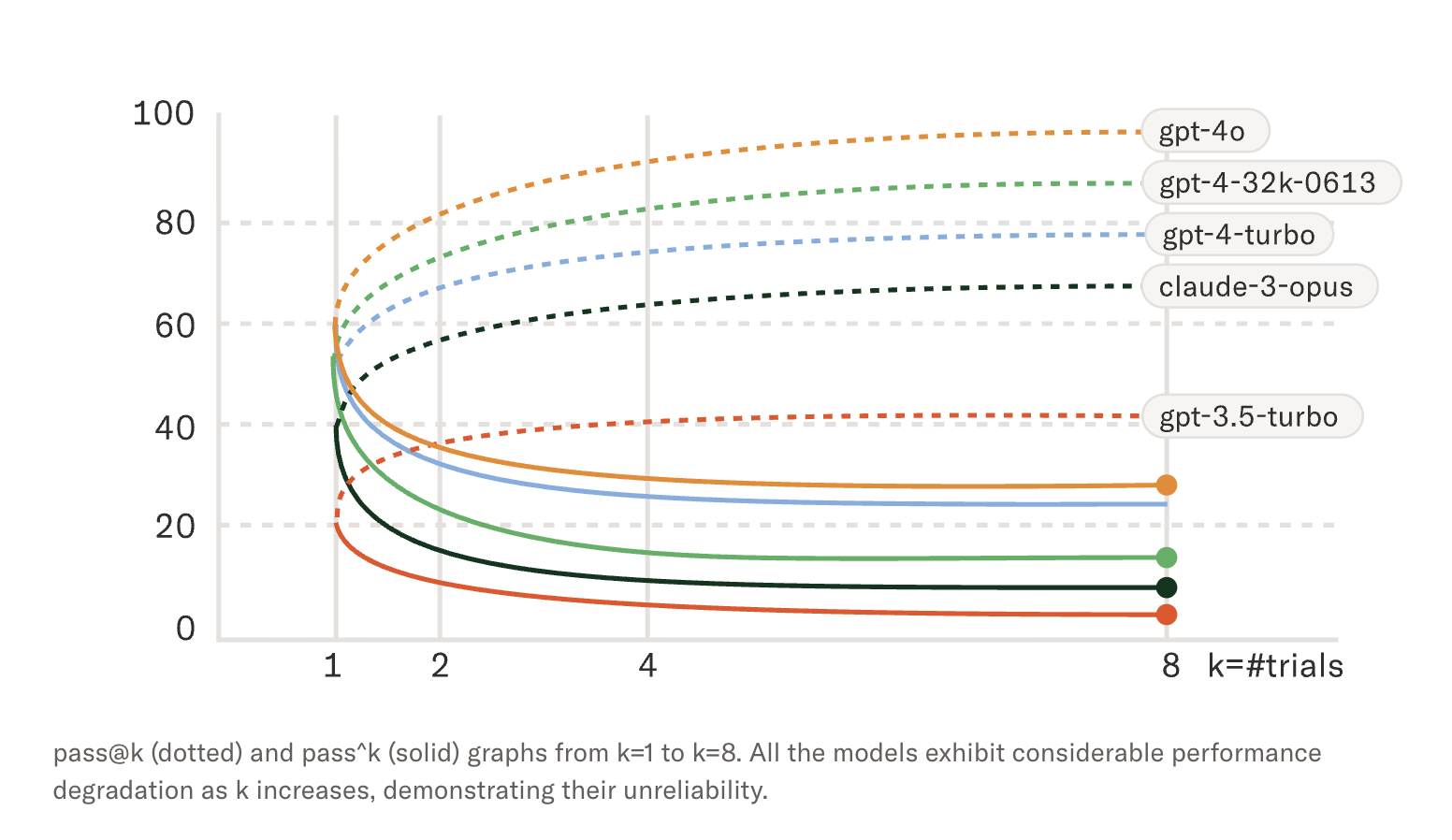

τ-bench asks a question most golden datasets assume away: does passing a test case mean the agent can actually do the task? The benchmark simulates a customer support agent, but instead of deterministic test cases, it runs variations of the same task. What they found: 81% agent accuracy starts to look different when you test it more than once. They introduced pass^k, the rate at which an agent can pass the same task k times consecutively, and GPT-5 dropped from 81% at pass^1 to 58% by pass^4.

Image source: Sierra AI - Benchmarking AI Agents. This image is reproduced for educational purposes and is not our own.

This means the agent didn't get worse because of harder tasks. It got worse on the same goals. If the same task can produce different results, then a test case isn't really a task. It's a sample from a distribution.

A fix based on one failing trace is tuned to that trajectory. Whether it holds across the distribution is a question you can't answer by running the same test again. You need something else, not quite unit testing, not quite traditional ML training, but something that borrows from both.

Addressing Hidden Overfitting

So what do you actually do? The oldest trick in the book still works: split your data into a train and test set. If your fix improves training but testing isn't going up, you know you've overfit. There are a couple of intricacies that make this different from traditional machine learning: namely, a lack of data, the need to test similar variations (à la τ-bench), and measuring meaningful improvement.

Building Test Buckets

τ-bench exposed the need for testing variations. Unlike unit tests, you want very similar tests that evaluate the same capabilities. We can call these groups of similar tests "buckets." For example: booking an aisle seat, booking a window seat, booking with a loyalty number, booking for someone else. These all test the same booking flow, so if your agent handles one but fails another, you've found a real issue with your distribution, not just a sample.

Making these buckets may seem time-consuming, but it isn't. Take each case in your golden dataset and generate ten variations with an LLM, or manually make changes by shifting the parameters, adjusting the phrasing, or changing the context slightly. A dataset of 50 cases becomes 500 without inventing new things to test. For the cases that flip-flop, add multiplicity (run the same test case multiple times). Now your golden dataset has grown from 50 closer to 750–1000.

The 50/50 Split

As we talked about earlier, we need a held-out test set. Since we want the test set to be representative of the train set, split the buckets 50/50. This might seem unintuitive, as traditional ML uses roughly 10% for testing, but golden datasets are small enough that you need more coverage on the test side to trust your signal. Additionally, we don't need all the data to train, since with buckets we don't need to expose the model to all the variations. That gives training a bit more leeway.

Modeling Improvement as Distributions

Once your numbers start improving, you need to parse the noise. Most teams check if "number went up," but that measurement generally has noise. Second-order thinking leads you to statistical testing (e.g., t-tests). But with the concepts of buckets and multiplicity, the independence assumption of t-tests is challenged.

A recommendation is to model the buckets as distributions themselves, or at least account for the correlation between test cases. Stay away from watching one big number move up and down. Instead, strive to see if a capability improved across all its variations.

Did the distribution shift? This tells you which capabilities actually got better and which improvements were noise.

An Ode to Hidden Overfitting

This problem has been generally unspoken in the literature because golden datasets carry the shape of unit test suites but the soul of training data. And training data overfits. With neural networks, you can watch it happen: training accuracy rises, test accuracy stalls, and the widening gap tells you to stop. With agents, the gap never appears. Tests pass, dashboards glow green, and everything whispers that you're on the right track.

This is hidden overfitting, the most dangerous kind, because it wears the mask of progress.

Principle 2: Climbing the Wrong Hill

After you've addressed hidden overfitting, you probably have buckets, a train-test split, and a way to measure whether your agent is improving. But are you improving on the right metric? Are you climbing the right hill?

The Optimization Trap

Golden datasets freeze at a point in time. The test cases you write before launch reflect what you could anticipate then, which is reasonable. But that snapshot becomes the target you optimize against, and every improvement pulls you closer to a benchmark that stopped evolving the moment you shipped. Judgment Labs calls this "climbing the wrong hill":

datasets undergo "single-time selection of examples and metrics that may remain unchanged for months" while the product evolves beneath them.

The question is whether this drift is theoretical or measurable. A recent study suggests the gap is both real and larger than most teams expect.

What Metrics Matter

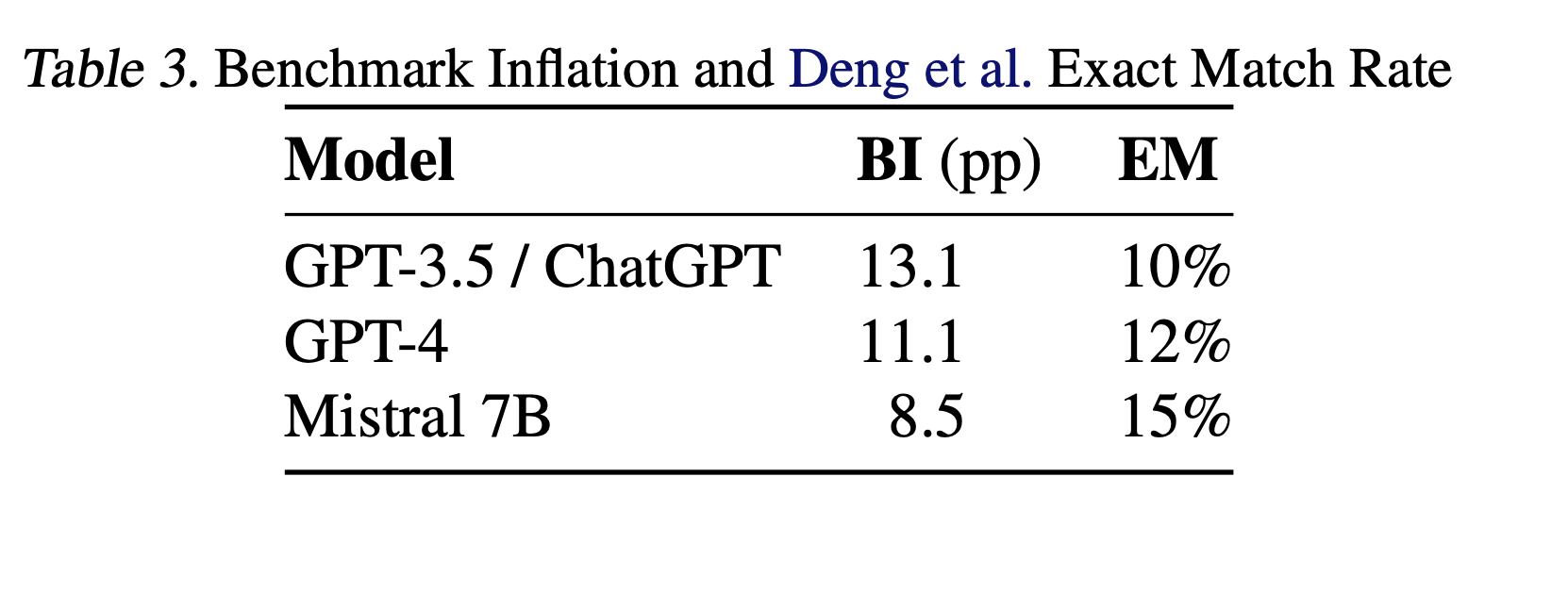

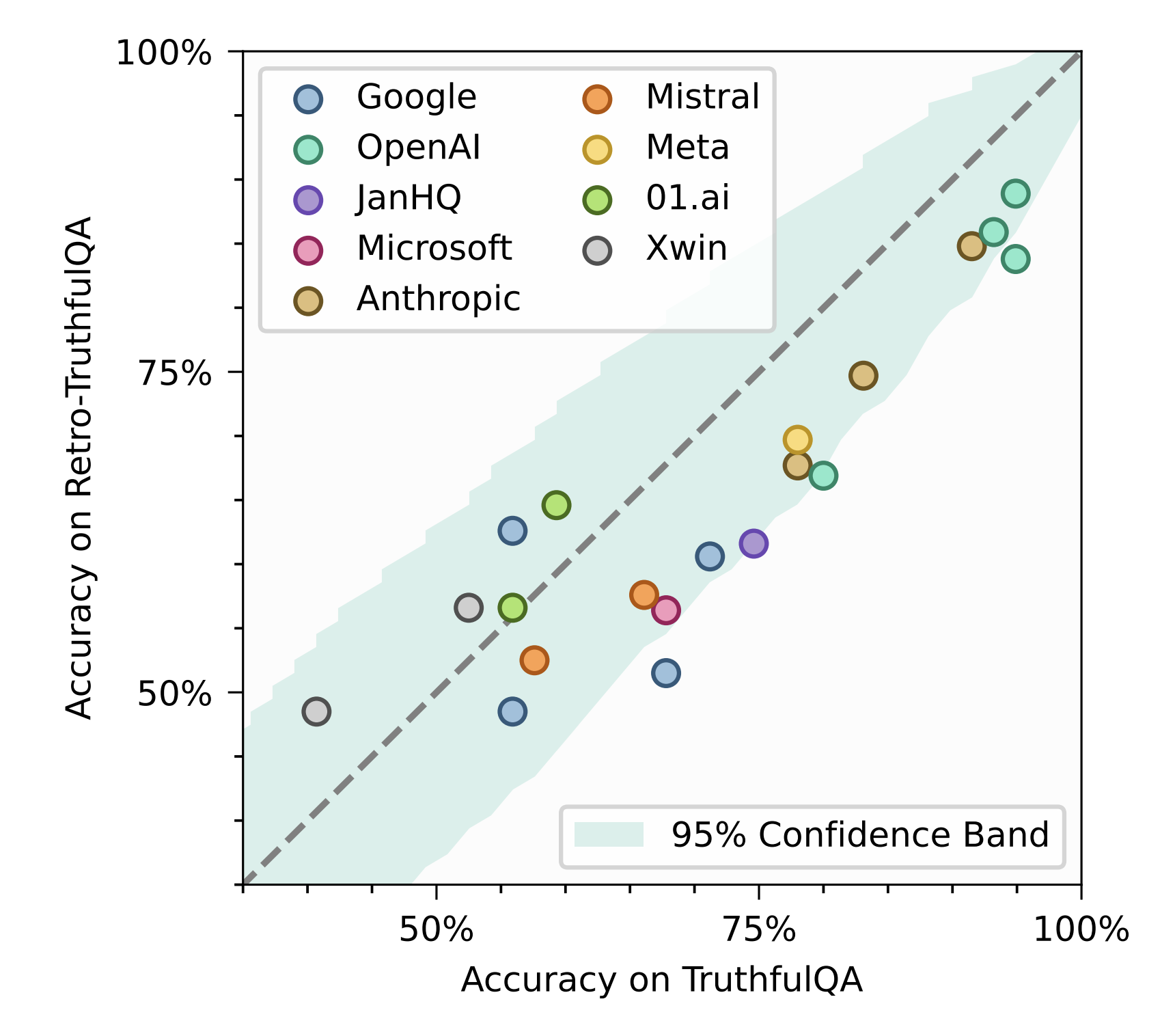

A team at ICML 2024 tested a simple hypothesis: what if public benchmarks no longer measure what they claim to measure? To find out, they created Retro-Misconceptions, a dataset statistically indistinguishable from TruthfulQA but never released publicly. Same distribution, same difficulty, but no chance of contamination through training data or iterative optimization.

When twenty models were tested against both datasets, the results were predictable but stark. GPT-3.5 showed 13.1 percentage points of inflation on the public benchmark. GPT-4 had 11.1. Some models hit gaps as high as 16 points. The pattern held across model families and sizes.

Image source: Benchmark Inflation: Revisiting Selection Bias in LLM Benchmarks, ICML 2024. This image is reproduced for educational purposes and is not our own.

Image source: Benchmark Inflation: Revisiting Selection Bias in LLM Benchmarks, ICML 2024. This image is reproduced for educational purposes and is not our own.

The implication is simple but uncomfortable: public benchmarks become targets the moment they're released, and targets get optimized against, intentionally or not. Training data includes benchmark examples. Prompts get tuned to known test cases. The score rises, but the underlying capability stays flat. You're not climbing toward better performance. You're climbing toward better benchmark performance, and those stopped being the same thing years ago.

Distributional Drift

Benchmark inflation is a contamination problem. Distributional drift is a time problem. The result is the same.

With every product change, every feature shipped, every workflow modified, how users interact with your agent shifts. This means the golden dataset you're optimizing against every day matters less than you think, because the real distribution has moved. You can keep making progress on your benchmarks, but it won't be progress on your product.

Closing the Loop

Before deployment, guessing is the only option. Afterward, you have something better: the actual distribution. The obligation shifts once production data exists.

The goal is to sample from production and convert those traces into replayable test cases. This usually means building a conversion layer, something that takes traces and metadata and plugs them into an environment that can simulate the interaction. If that infrastructure feels out of reach today, start smaller. You don't need to climb Mount Everest on day one; sample inputs and mock dependencies if you can't grab full user state. Just start somewhere. Imperfect replay still beats imagined scenarios.

The benchmark inflation study showed what happens when you measure against a target that's drifted from reality: gaps of 10–16 percentage points that nobody saw coming. Your golden dataset doesn't need to be that wrong to cost you. Even a few points of hidden drift compound over time, and unlike overfitting, nothing in your dashboard will warn you.

The Research-Practice Gap

Even if you've solved both problems (noisy measurement and a stale test distribution) the question of what to actually change is its own research problem. The literature on agent performance keeps growing. Most teams building agents haven't read it.

Hypotheses, Not Facts

These findings aren't facts about your system. They're hypotheses. Osmosis AI found that structured output mode degrades reasoning: GPT-4.1 dropped to under 3% accuracy on math problems when JSON output was enforced. Manus argues that KV-cache hit rate directly controls latency and cost. Anthropic discovered that loading only 3–5 relevant tools per query improved Opus 4's accuracy from 49% to 74%.

Each of these might apply to your agent, or it might not. The only way to know is to test it.

One Variable at a Time

So how do you test it? The same way your high school chemistry teacher insisted on: isolate one variable, hold everything else constant, measure the effect. Test whether structured outputs hurt your accuracy before you test whether tool selection helps. Change one thing. Measure. Change the next.

This is slow. There's no way around it. Each hypothesis requires enough runs to get past the stochastic noise, and enough coverage of your test distribution to trust that results will generalize. A single experiment might take days to run properly. And there are dozens of hypotheses in the literature, with more every month.

Slow Is the Point

Most teams don't do this. They change multiple things at once, ship when the numbers look better, and move on. This is how you end up climbing the wrong hill. You don't know which change helped, which hurt, and which did nothing. You've generated motion without generating knowledge.

The teams that get this right treat every change as a hypothesis and every deploy as an experiment. Yes, it takes more time. But when something improves, you know why. When something breaks, you know where to look. The slowness isn't overhead; it's the mechanism that produces durable results. Speed is how you end up optimizing the wrong thing. Rigor is how you know you haven't.

Our Philosophy

The future of AI Agents is one where they automatically improve, learn, and train in the background.

The Gap That Remains

Even if you do everything right (production-sourced test cases, multi-pass measurement, variable isolation) the work compounds. Every new technique to evaluate, every model update, every shift in production traffic is another round of experimentation. The teams that sustain this kind of rigor tend to have dedicated evaluation infrastructure and the engineering bandwidth to maintain it. Most teams don't. And the gap between what rigorous improvement requires and what teams can practically sustain keeps widening.

The scientific method doesn't stop working because it's slow. It stops working when teams can't sustain it. The question isn't whether to be rigorous. It's whether rigor can run on its own.

What would that look like? An agent that improves systematically, not through guesswork. Hypotheses tested in the background, one variable at a time, with enough repetition to trust the signal. Changes you can trace back to evidence. Not a black box that gets better for unknown reasons, but a system that learns and shows you why.

This is the future we're building toward at Lucidic. Agents that automatically improve, learn, and train in the background, through visible changes you can see and understand. But we think the path runs through everything this post describes: production-grounded data, distributional testing, and the patience to isolate what actually works.

Written by Abhinav Sinha

Thanks to Anvit Sinha and Sri Jaladi for talking through a lot of these ideas and challenging my assumptions. Thanks to the rest of the Lucidic AI research team for helping put this together.

%20(2).DYlGygaK.png)